By Daniela Bridges

When most people think of Brazil, they picture soccer, samba, stunning landscapes, and vibrant culture. What many don’t realize, though, is that behind this beauty lies an incredibly dark past—a history that still casts a shadow over the country today. Between 1964 and 1985, Brazil was ruled by a military dictatorship whose primary goal was to maintain power through censorship, torture, and exile. During this period, music became an unexpected battleground, where artists used their work to fight for freedom and preserve their Brazilian identity. Growing up in a family with Brazilian roots, my mom being from Brazil, and my grandfather and uncles serving in the Brazilian military – I was always aware of the military dictatorship. However, it was a sensitive topic that was honestly rarely discussed in our family, as it was for manyvBrazilians, so I truly didn’t know much about it. That changed this year when the film Ainda Estou Aqui (I’m Still Here) was released. The film, which explores the emotional and historical impact of Brazil’s military dictatorship, became a worldwide cultural phenomenon and even won an Oscar for Best International Feature Film. Watching this movie sparked my curiosity and prompted me to dig deeper into the history of the dictatorship, which is what eventually made me decide to write this paper on it, in a way giving me an excuse to learn as much as I can about it.

The music during this time in Brazil served as a tool for both resistance and cultural preservation while simultaneously giving the Brazilian people a place to escape. The military dictatorship, which started in 1964 in Brazil, was one of the most pivotal moments in the country’s history. The president at the time was João Goulart who was a Democrat and was widely known, and widely hated, for his series of left-wing reforms. In March of 1964, a group of military leaders and conservatives, who were actually backed by the United States, overthrew President João Goulart. After this coup, this group of people eventually established an authoritarian regime that we know lasted until 1985, twenty-one whole years. To be quite honest, I was not completely aware of what exactly a military dictatorship was until this year. These new groups of leaders essentially had control over the whole country including the people in it. Not just what the people of Brazil did, but their public beliefs, the media they consumed (including music), and overall suspended their political rights. They also had the power to arrest, torture, and/or exile anyone who they deemed a threat to their regime, which we see in the film Ainda Estou Aqui. The film very graphically shows music censorship like military officers entering a home and checking a family’s stack of records to see what kind of music they were listening to, and a group of people getting pulled over by the police and then checking what

type of music they had in the car. When you watch the film, you see how these moments serve as stark reminders of how the dictatorship sought to regulate not only the political discourse but also the very culture and expressions of its very own people.

The Departamento de Censura of the Departamento De Polícia Federal Do Brasil was a department that was created to censor the media that the people of Brazil consumed. Their main job/goal was to ensure that no music, television, movies, etc, contained progressive views that went against the regime. If the music did go against the regime, it was immediately vetoed and the musician and or anyone who was associated with the creation of the music were most likely kidnapped and faced enormous consequences. While conducting my own personal research and speaking to my Mom about what she remembered about this time, I asked her if she knew or remembered anything about this specific department. She actually told me that her aunt, my great-aunt, was the head of one of the wings of the Departamento de Censura. My Mom remembers her and her siblings getting invited to concerts in Sao Paulo, the largest city in Brazil, by this aunt. One of her primary roles in her job was to attend concerts of famous musicians and ensure that they followed the rules and stayed within the guidelines of the regime. The way that musicians got around this was by creating music that heavily used metaphors and symbolism.

Amid the regime, a genre of music came to the scene that challenged everything about Brazil’s cultural norms, with an extremely experimental style blending traditional Brazilian sounds with global influences known as Tropicalia. The genre Tropicalia has some of the most iconic, and my personal favorite Brazilian songs like Mas, Que Nada!, A Menina Danca, Água

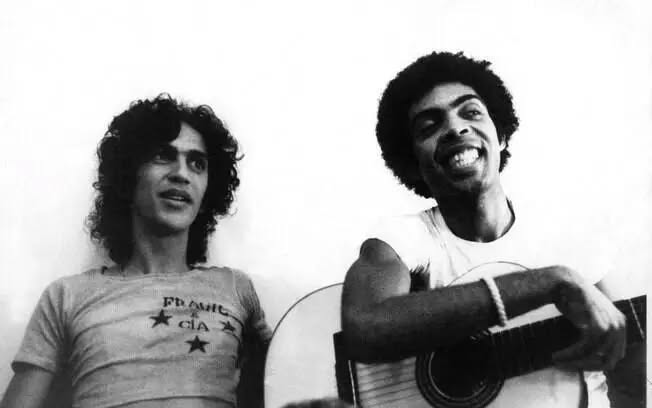

de Bebe, Flor de Lis, and the list goes on. These songs, along with the hundreds I didn’t list, were the sounds that gave millions of Brazilians an escape and release during these two decades. Tropicalia was all about honoring the traditional Brazilian style of music while challenging political authority. This genre of music became so well known and widespread that many people listening to this music didn’t realize that they were listening to “controversial” music. “The musical aspect of Tropicália was spearheaded by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, two songwriters from the state of Bahia. The change campaign took inspiration from Oswald de Andrade’s “Cannibal Manifesto,” which advocated for “cannibalizing” foreign cultural influences and making them into something distinctly Brazilian. Tropicália musicians followed de Andrade’s suggestion by combining traditional Brazilian music with psychedelic rock by groups such as The Beatles and avant-garde composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen. The result was a melding of local and international influences, ultimately creating an entirely unique style

of music.” (Golden, 2024)

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were the key artists for Tropicalia and were the leading figures other artists followed. On December 27, 1968, both Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were taken and kept imprisoned for two months, along with many other artists of the Tropicalia movement. After this time in prison, they were exiled from the country and fled to London, as many other Brazilians did during this time. Even after they were exiled and moved to the UK, they were still widely recognized global influences, and would perform at festivals or small concerts throughout the world. They gave hope to not only the Brazilians who were still living in Brazil but all of the Brazilians who lived abroad. Overall, this genre’s global influence created a cultural dialogue between Brazil and the rest of the world, which ultimately showcases how music can transcend borders and connect people, even across continents, during those times.

Apesar de você by Chico Buarque is one of Brazil’s most iconic protest songs released in 1970, six years after the military dictatorship began. When you first listen to this song, it may sound like a love song, as many still believe it is. However, upon digging deeper and analyzing the lyrics, a much more layered meaning emerges. While the lyrics don’t directly address

politics—to avoid the scrutiny of censorship—when you approach it through the lens of a protest song, the message becomes abundantly clear. “Apesar de Você”, which translates to, “In Spite of You”, is the ongoing lyric in the song, Apesar de você, amanhã há de ser outro dia” (“In spite of you, tomorrow will be another day”). The “you” in the song is not referring to a romantic figure, but the regime. This specific line symbolizes resistance and hope, in a way implying that no matter how much control the regime has over the people, a change is going to come soon. The most powerful line in the song, in my humble opinion, is “Como vai proibir quando o galo insistir em cantar?” (“How will they forbid it when the rooster insists on singing?”). I interpret the rooster as the people of Brazil and the inevitability of change and freedom. This represents the persistent nature and eagerness to fight back and not bend. By using nature and love as metaphors, Chico Buarque subtly (but not so subtly) critiques the military dictatorship’s attempts to control the lives of the Brazilian people.

This song gave people hope, all 3 minutes and fifty five seconds of it. It’s living proof that music does have the power to inspire change in people.“Most songs are three minutes long. It is possible yet difficult to capture a major issue in such a short time capsule” (Weissman, p. 321, 2010) When I read the section of the book which speaks on protest songs, I was initially

conflicted. Could a three or so minute song really inspire social change? It made me think back to my own experiences and those around me. Long story short, yes, I do think music has the power to motivate people, spark conversations, and even challenge oppressive systems, like the one in Brazil. Today, Apesar de você is widely recognized as one of the most Brazilian songs of all time. I know non-Brazilians, who love this song and it’s one of the only Brazilian songs that they know, even if they aren’t fully in tune with Brazilian music.

The next song I’m going to touch on has an undeniable relevance in Brazilian protest music and got a second life when it was featured in Ainda Estou Aqui. The 1972 song, É Preciso Dar um Jeito, Meu Amigo (“It’s Necessary to Find a Way, My Friend”) by Erasmo Carlos is yet another song that subtly critiques the military dictatorship. With an almost unsetting rhythm and some key lyrics like:

Eu cheguei de muito longe

E a viagem foi tão longa

E na minha caminhada

Obstáculos na estrada, mas enfim aqui estou

Mas estou envergonhado

Com as coisas que eu vi

Mas não vou ficar calado

No conforto acomodado como tantos por aí

É preciso dar um jeito, meu amigo

(Which translate to)

I came from far away

And the journey was so long

And on my way

Obstacles on the road, but finally here I am

But I’m ashamed

Of the things I saw

But I won’t stay silent

In the comfortable accommodation like so many out there

We need to find a way, my friend

Erasmo Carlos was very careful to navigate the narrative in this story in a way where he could release it without the risk of being exiled, like so many of his artist peers before him. He subtly touches on the way musicians had to navigate the strict censorship laws and find ways to hide deeper meanings in the lyrics. The line “Mas estou envergonhado com as coisas que eu vi” which translates to “But I’m ashamed of the things I saw”, can be interpreted as the shame and disillusionment many Brazilians felt towards the things they would casually witness. Another key aspect Carlos touches on that is unique to this song, is the journey many people took to build a life in Brazil, only to witness how the country changed drastically under the dictatorship. This song became the anthem of the film Ainda Estou Aqui and is still riding on the second life it got from it, even being featured on Brazil’s Hot 100.

There are many things I love about my Brazilian culture, but if I had to choose one thing that stands out the most and has made the largest impact on me, it would undeniably be the music. There’s something about Brazilian music—just like all music— (but specifically Brazilian) that has the power to bring people from completely different backgrounds together, and create this unspoken connection. Growing up, my mom would always have Brazilian music playing in the house on our record player. One story she told me that always stuck with me was about the sort of “underground” house parties she and her friends would go to in the early 80s in Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro. At that specific time, the military dictatorship still had such a tight grip on what could and couldn’t be said, which still included music. Songs with even the slightest bit of political criticism or messages of resistance were still censored, which meant that a lot of artists couldn’t perform in bars, clubs, or any public venues without the risk of being taken by the police. So instead, they found other ways to share their music like performing in

houses/apartments. My mom and her friends would go to these house parties in Ipanema where local musicians would perform almost every weekend. I’m sure there are countless examples similar to this one of how music found a way to exist and persist, just like the people.

The music that was created during the twenty-one years the military dictatorship lasted in Brazil, is still continuing to have a lasting impact not just on Brazil as a country, but the whole world. The country of Brazil, specifically Rio De Janeiro, has been the topic of conversation on the internet as of late, with people debating on whether it’s safe to visit, the trending music, and the cultural influence it has always had and continues to have. Brazil’s music scene remains one of the most influential in the world with genres like bossa nova, samba, and funk. It’s amazing to see these genres hit mainstream media in places like the United States and become a topic of conversation, as it was during the dictatorship. Despite the challenges the Brazilian people faced during those trying times, its music continues to be a testament to the country’s enduring strength. It’s yet another reminder that music has the power to unify, resist, uplift, and leave a lasting legacy. In the words of Fernanda Torres, in her acceptance speech for winning Best Female Actress at this year’s Golden Globes for the film Ainda Estou Aqui, “This is proof that art can endure through life even in difficult moments”.

References

Golden, W. (2024, September 9). Songs of protest: Tropicália and countercultural music in 1960s

Brazil. Afterglow. https://www.afterglowatx.com/blog/2022/3/27/songs-of-protest-tropiclia-and-countercultural-music-in-1960s-brazil

Weissman, D. (2010). Talkin’ ’bout a revolution: Music and social change in America. Backbeat

Books, an imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation.

YouTube. (n.d.). FERNANDA TORRES WINS FEMALE ACTOR MOTION PICTURE AT THE

GOLDEN GLOBES. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hd51WL2EK38