by Sydney Fisher

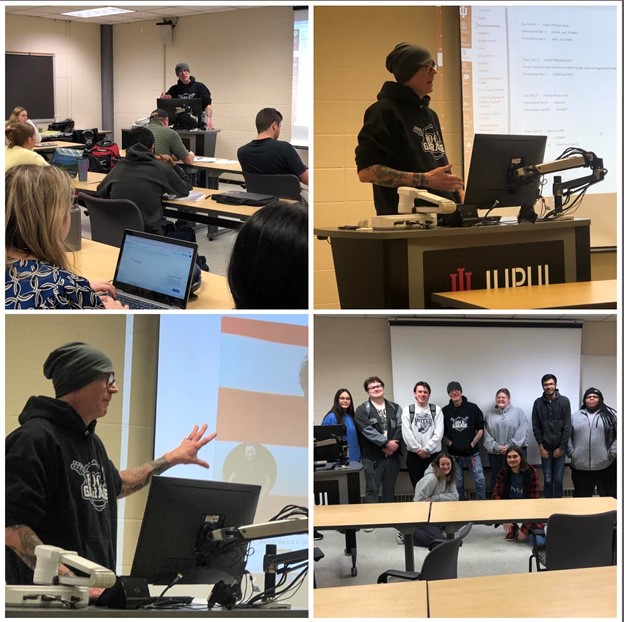

Indiana University Indianapolis’ “Rhythm & Revolution: Music and Social Change” course is the brainchild of our impassioned, courageous and inspiring leader, Trevor Potts. Emblematic of his devotion to us students, he has delivered upon his promise, week after week, to supply us with impactful guest speakers. To wrap up our Rock & Roll unit, Trevor decided on Preston Nash, former member of the punk band Dope and current founding member of Rock Garage Music in Indianapolis. In one of those funny full-circle moments that life affords you sometimes, Trev chose to show us Dope’s “Die MF Die” (2001). I’d heard the song once before. As a young, troubled teen–enrolled in a group of young, troubled teens–a girl who I did not understand but who I found endlessly fascinating brought in the song for our music therapy day. Just as we’d done with everyone else’s, hers was played loudly and twice. Not only did I get the pleasure of watching our counselor squirm as they listened to the song, but I also got to experience the thick, hilarious awkward state of the room that existed while she read the read the lyrics aloud for us all.

In keeping with the theme, as guest presenter Preston brought the IUI Rhythm and Revolution class two protest songs to examine by comparison. One was Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The U.S.A.” (1984) and the other, to my pleasant surprise, was Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” (1939). He started with Springsteen, as climax-building required. Ironically, Springsteen’s anthem is synonymous with American culture. And that was exactly Preston’s point in bringing this song truly to our attention. The mention of Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” had everyone primed to be curious, and so we listened more closely to this first song, even though we all knew it so well! Right? Wrong.

The patriotic plundering of drums and the prideful, self-indulgent chorus sounded different for the first time to some of us. We had access to more critical thinking skills than we perhaps had when we heard this song for the first time, and Preston was prepared to take advantage of that. He played the music video along with the song. The video was essentially a montage of reels showing Vietnam War veterans in an unfortunate, arguably avoidable state that they’d fallen into after their return to the States. By examining its lyrics, as a class we were able to recognize the song as an attempt at protest. More importantly, we got to examine why it failed. Led by Preston, we discussed how, despite the song’s scathing lyrics, it became emblematic of patriotism and a part of many of our childhoods burned deeply into our brains. It was catchy. It was loud. And as Preston made sure we understood, it gave white people permission to enjoy and ignore.

In pointed comparison, up next was Holiday. We listened to “Strange Fruit,” and Preston told us many important things about the song’s creation and, in terms of its life as a piece of protest, its creator. We learned about how the lynchings of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith inspired Abel Meeropol to write his poem “Bitter Fruit” in 1937, and how that poem was later sung and recorded by the iconic Holiday. The men who were lynched in the very state where many of us had been raised, or at the very least, the crime happened in same state that we were all paying to live in in some way or another. Nash told us about the conditions under which “Strange Fruit” required to be sung; low lighting and locked doors set the stage for a haunting quiet from which no white listener could escape. Unlike Springsteen’s dopamine-heavy tune, “Strange Fruit” offered white audiences no such respite or reprieve.

You could see how disappointed Preston Nash was when his time was up, and the many audience members staying after the session indicated that we were too. It was a fantastic opportunity for our class to dive deeper into the substance of each song. In doing so, we got to learn more about someone deeply influential in promoting wellness and collectivity in Indianapolis through music.